George Weissbort (1928-2013), Still life with a statuette and pink roses

The impact of the classical past on the art of the Renaissance, as well as upon literature, politics, philosophy and rhetoric, was so cataclysmic as to echo down the centuries with a continuous rumble until our own day.

Domenico Ghirlandaio, Adoration of the Shepherds, 1485, Sassetti Chapel, Santa Trinità, Florence

By the 15th century the remains of Roman architecture which surrounded and filled the cities of Renaissance Italy were being incorporated into religious paintings as the setting for nativities and annunciations. Ghirlandaio’s Adoration takes place in the ruins of a classical temple, which has been converted to a stable by means of a rickety framework of withies, tied together and holding a roof of battered planks on top of the remaining pillars, and the animals of the Nativity eat from a classical sarcophagus. These relics of the classical world – as well as providing a dignified and beautiful setting – simultaneously stood for the order of the Old Testament, crumbling and ruinous when set against that of the New, in the shape of the infant Christ.

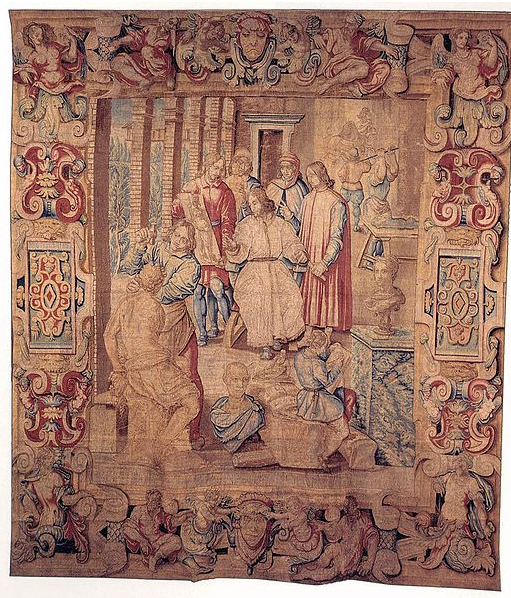

Johannes Stradanus, Lorenzo de Medici in the sculpture garden, 1571, tapestry, Museo Nazionale di San Marco, Pisa

Lorenzo de’ Medici kept some of his own collection of Greek and Roman pieces in a ‘sculpture garden’ which, according to Vasari, became a kind of academy for artists, who gathered to draw and otherwise copy these fragments of classical art. Michelangelo is said to have produced a carved copy of a faun so perfect that it attracted Lorenzo’s attention, and launched the young Michelangelo on his long, classically-saturated career.

This was an archetypal early academy which would provide a model for subsequent methods of teaching drawing, painting and sculpture, whether in the artist’s workshop, or in a more formal setting. The proportions and poses of classical statuary, whether in the original Greek pieces or in Roman copies, were seen as encapsulating the ideal proportions and forms of the human body, and therefore were the perfect models for depictions of Christ, the Madonna and the saints. They were also, of course, appropriate models for the gods and goddesses in paintings of mythologies, and they provided a guide against which all other figure painting and even portraiture might be set.

Attributed to Johann Zoffany, The Laocöon Group, 18th century

By the 18th century, the use of classical sculpture – and, where not available, of casts taken from the originals – was a central pillar of the national academies of painting and drawing which were beginning to emerge from their more informal prototypes. Pieces like the Laocöon, which had been cast several times since first being discovered in 1506, were dispersed in replica form through much of Continental Europe, as well as Britain and Ireland, and were copied in pencil, charcoal, paint and in three-dimensional media. This could be considered the high point of still life painting; the ultimate test of an artist’s skill, and one of the most desirable souvenirs for a Grand Tourist to bring home – if he couldn’t acquire a marble replica.

In any group of paintings by artists trained through traditional methods in the ateliers and academies of the 19th century, sculptures and casts would form a significant presence, and the work of the artists in Mark Mitchell’s collection is no exception. George Weissbort, for instance, who was deeply influenced by the work of the Old Masters from various periods, took the elements of compositions from his favourite painters, and remade them in his own idiom.

Chardin, Still life with attributes of the Arts, 1766, Minneapolis Institute of Arts

Chardin’s vivid representation of the arts of painting, architecture, sculpture, drawing and metalwork, symbolized sculpture by a figure of Hermes, messenger of the gods, made by Chardin’s friend Pigalle, but based on actual classical models. This evocative and beautifully-balanced composition was remade by Weissbort as Dance of the Three Graces to trumpets & viol (now sadly sold from the Collection).

George Weissbort, Dance of the Three Graces to trumpets & viol

Here, he celebrates the aural arts, with musical instruments, sheet music, and a statuette of the Three Graces who seem to be listening to celestial music, and to be poised on the brink of dance. Terpsichore, the muse of dance, usually carries a lyre, whilst Euterpe, associated with music, has a double flute, the equivalent here of Weissbort’s trumpet and viol; whilst the Muses when dancing often have flying ribbons or scarves.

George Weissbort, Still life with a statuette and pink roses

George Weissbort, Still life with a statuette and pink roses

A much more modern Master provided the inspiration for another of Weissbort’s statuary still life arrangements; he turned to Cézanne’s work at various points in his career, and the influence of the Post-Impressionist can be seen in Weissbort’s landscape paintings as much as in more overt examples such as this.

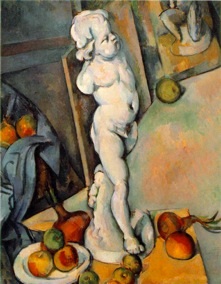

Cézanne, Still life with plaster cupid, c.1895, Courtauld Institute of Art

Both works use a statuette of a small boy on a table-top, accessorized with drapery and natural objects; Weissbort has, however, remade Cézanne’s work in the spirit of the 18th century Rococo, arranging the table symmetrically, viewing the statue frontally, and creating a stable and balanced composition in place of the shifting vertiginous planes of the Cézanne. It is almost as if Cézanne’s painting has been visualized through the eyes of Chardin, presenting a calm and rational version of what had been questing, experimental and urgent. Weissbort has also once more ‘feminized’ his subject, with brocade, pink roses, and soft warm tones replacing the severe blue cloth, geometric fruit forms and vibrating colours of Cézanne’s work.

Other artists in the Collection who have looked again at the classical components of their training, and decided to subvert the whole subject, include – for example – Dudley Holland. Holland taught art at both Willesden and Harrow Schools of Art, and at Goldsmiths, University of London. In 1949 he became principal of York School of Art and Design, and in 1951 of the Guildford School of Art (now the Surrey Institute of Art and Design). He was thus ideally placed to comment on the use of sculpture and cast drawing as an element of artistic training.

Dudley Holland (1915-56), A corner of the studio, s & d 1947, RA 1948

In his still life painting, A corner of the studio, he has taken the horizontal axis of Chardin’s Still life with attributes of the Arts, above, repeating the rolls of paper, drawings and books of the latter. But the classicizing sculpture, through which Chardin was expressing the seeds and derivation of his own art, is replaced by an abstracted, ‘primitive’ sculpture, and the head of a fashion mannequin. Holland is creating a subtle reminder of other influences than the classical which began to appear in the work of artists at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries – the role, for instance, of early African sculpture, which was important for both Picasso and Gauguin. He is also noting the place in a commercial world of representations of the human form: the use of ‘casts’ or models in shop windows to sell fashion, rather than in art galleries, to elevate the spirit.

Denys George Vesey Wells (1881-1973), Still life with statuettes of the Buddha and Thai temple dancers

Another artist who seems to enjoy subverting the classical tradition, and the use of classical objects in still life painting, is Denys Wells. Wells is noted for the watercolours he made of bomb-damaged streets throughout London, during and after the second World War, becoming known as ‘the recorder of London’. Possibly as an antidote to this grim work he produced vibrantly coloured still life paintings, many of which have a whimsical element – as here, in the group of little brass temple dancers, lined up before a laughing Buddha as though about to perform a can-can.

The classical past thus provides an infinite and adaptable vocabulary of images, which can stand for the pagan past as against the Christian present; express an ideal model for the human body; symbolize ideas, virtues and states; clarify artistic striving (like Cézanne’s); act as a pointer to new influences; satirize modern consumerism; and laugh at its own dignity. Where would our art be, without that classical cast?

Mark Mitchell Paintings & Drawings specializes in 19th and 21st century British and Continental fine art, including still life paintings and landscape paintings. For more information, or to make an enquiry regarding either of the aforementioned still life paintings, please do not hesitate to contact Mark Mitchell by telephone on 0207 493 8732.