Throughout history, humans have been fascinated by the human form and have displayed this interest through the use of art. Just about every artist from Pablo Picasso to Michelangelo has explored the complexity and beauty of the human figure, but how has this changed over the ages and why are we so fascinated by the body?

Albert Ludovici Jnr, Monsieur Coulon’s Dancing Class

Portraiture remained popular throughout the centuries as the wealthy commissioned for their likeness to be immortalized on canvas. This developed into paintings that could tell the story of an individual or group and continues to evolve and change from the romanticism of the 18th and 19th century, to the expressionism and surrealism of the 20th century.

Robert Greenham, Tango Final of British Championship, Blackpool

The invention of the camera had a huge effect on the way in which artists approached their figures. It gave the freedom to represent the human form in everyday situations that may not have been possible when the subjects were required to model for their artist in order to create a realistic portrait.

David Oyens, Young Woman Reading in the Studio

Many artists have achieved the goal of creating highly emotive pieces just by representing the human form. Everything from the pose to the colours to form can evoke a whole range of emotions in the viewer that may be harder to create in still life paintings, for example.

Stephen Rose, Leticia Reclining

But what is it that we find so fascinating about the human body in art? Perhaps it is the versatility of the subject, whether it is in the form of a nude that represents vulnerability or as a sculpture, showing a strong and muscular figure. There is so much that can be embodied in the human figure and so many messages that can be conveyed.

Albert Ludovico Jnr, The Recital

It is clear to see that we remain just as fascinated with the human figure as we ever were. We continue to share an enjoyment in displaying the beauty of our own human nature, and it seems as though this will carry on for centuries to come.

Bertram Nicholls, The weir at Windsor

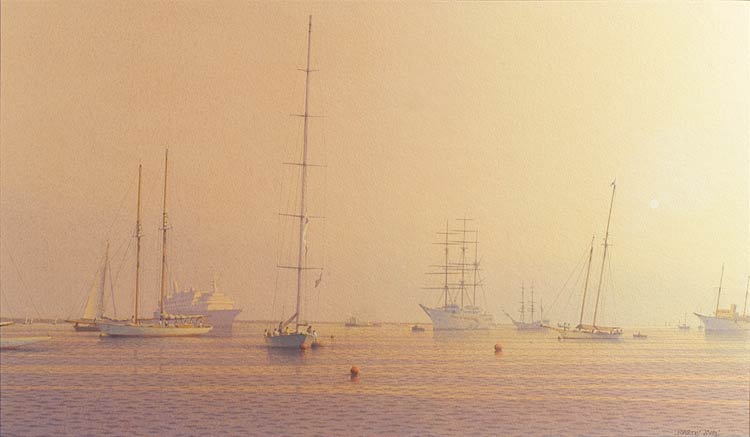

Bertram Nicholls, The weir at Windsor Alfred Olsen, Shipping along the coast

Alfred Olsen, Shipping along the coast Albert Ludovici, Jr. Monsieur Coulon’s dancing class

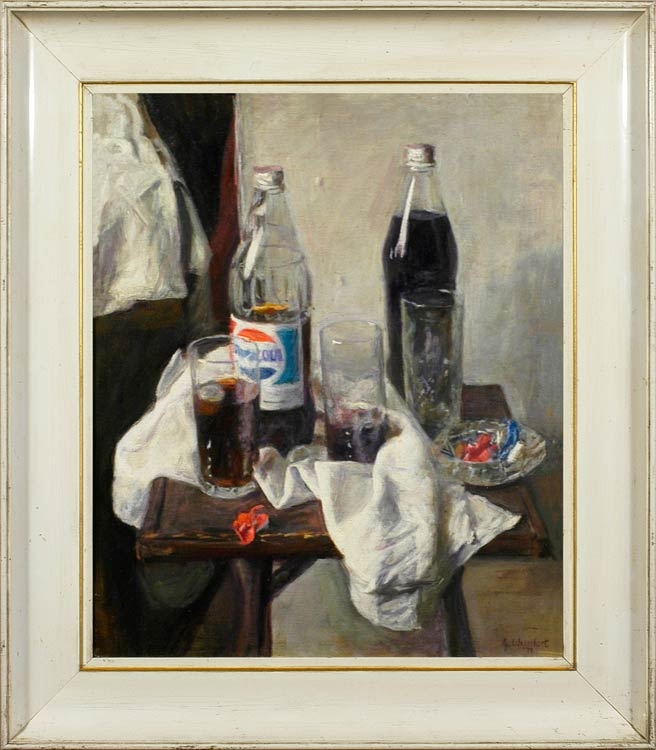

Albert Ludovici, Jr. Monsieur Coulon’s dancing class George Weissbort, In the studio: a break for Pepsi

George Weissbort, In the studio: a break for Pepsi Stephen Rose, Cherries in a foil container with a glass

Stephen Rose, Cherries in a foil container with a glass

Stephen Rose, Nude, standing, looking left

Stephen Rose, Nude, standing, looking left Stephen Rose, A tray of eggs

Stephen Rose, A tray of eggs