Original bookplate for A. Ludovici, An artist’s life in London and Paris 1870-1925, 1926, with the coat of arms of the Ludovici family

Original bookplate for A. Ludovici, An artist’s life in London and Paris 1870-1925, 1926, with the coat of arms of the Ludovici family

The members of the Ludovici clan were international in their roots, their lives and their education, and one branch settled in England during the 19th century. This produced three generations of artists between 1820 and 1971, all of whom were trained and/or worked on the Continent, whilst remaining based in Britain. The family traced its origin to the Ludovisi of Bologna, one of whom – Ludovico Ludovisi (1595-1632) – was a cardinal and connoisseur, who built the Villa Ludovisi (mainly demolished in the 19th century) to house his collection of classical and Baroque sculptures.

Piranesi, Veduta di Villa Lodovisi, 1748, etching; from Varie Veduti de Roma Anticha e Moderna

The first generation of the Ludovicis to settle in England was Albert Johann, who had been born in Saxony in 1820. He moved to Paris in his early twenties to train as an artist at the Atelier Drölling, where amongst his peers was the Englishman Roger Fenton, who would become one of the first war photographers. In the late 1840s Albert Johann travelled to England where he settled, marrying a Parisian woman, Caroline Grenier, in 1850.

Albert Johann Ludovici (Ludovici senior; 1820-94)

Albert Johann Ludovici (Ludovici senior; 1820-94)

His main sources of income seem to have been portraits and decorative paintings in interiors, but he is also known for his genre and costume subjects. Although he is relatively obscure today he was in demand in his lifetime, and was even commissioned to paint portraits of the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII) and his bride. His portrait of the chemist and physicist, Sir William Crookes, is in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery. According to his son, one of his paintings, rejected from the 1863 Paris Salon and hung in the Salle des Réfusés, was bought by the Emperor Napoleon III, as a souvenir of his sojourn in London (it was a genre scene, of crossing-sweepers, called The last day of an old hat)[i].

Albert Ludovici senior, Sir William Crookes, c.1884-85, National Portrait Gallery

Albert Ludovici senior, The Puppeteers, 1876. Art Market 2013

Albert Ludovici senior, The Puppeteers, 1876. Art Market 2013

Albert senior exhibited with the Society of British Artists, becoming treasurer of the society. He had five children, of whom his namesake, Albert junior (1852-1932), was born in Prague (although he spent most of his life in England). Albert junior took after his father:

‘My childhood was spent more in my father’s studio in London than in the nursery. Washing paintbrushes and polishing the palette were occupations familiar to me from an early age…Drawing and painting were my occupations long before I learnt to write’[ii].

When he was twelve he was extracted from his local school and his father’s studio and sent to Geneva for five years, where he found himself at school with the son of Samuel Smiles (author of Self-help), and Lord Kitchener’s brothers. But at 17 he persuaded his father to let him attend a London art school, and the next year to go to Paris. He started out in the studio of one of his father’s friends, Emile Bin, who had been commissioned to produce classicizing murals for Zurich University and the theatre of Rheims, and in the evenings he studied at the Académie Charles. He then graduated to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, where his teachers included Cabanel, Gérôme and Isidore Pils, and his fellow students Gervex, Forain and Bastien Lepage. In September 1871 the Prussian army laid siege to Paris, and – like Monet, Daubigny and Pissarro – Albert junior left France to return home, where he helped his father to paint the interior of the Britannia Theatre, Hoxton, with decorative figures.

Interior of the Britannia Theatre, Hoxton, London, 19th century

Interior of the Britannia Theatre, Hoxton, London, 19th century

After the war he went back to Paris and worked as a portrait painter, but with his marriage in 1875 he settled in England. One of his regular sources of income was as a teacher – but, in an unusual and almost revolutionary step, Ludovici concentrated on female pupils. Amongst these was Lady Colin Campbell (née Gertrude Blood), art critic, biographer of fish and multiple adulterer, who, with Eva Gordon, attended ‘the art classes of Albert Ludovici at his studio in Charlotte Street’[iii]. Looking at Albert junior’s dapper photos, one can only speculate as to whether he became another scalp amongst many on Gertrude’s belt.

Albert Ludovici (Ludovici junior; 1852-1932)

In 1878 Ludovici followed his father into the Society of British Artists:

‘A picture I had just completed of Mr Coulon’s dancing class had been seen by several members of that Society, who informed me that if I would exhibit the picture they would make me a member. This picture and its companion, Signor Cruvelli’s singing class, were afterwards reproduced, as was the custom in those days, by etching… and published by Messrs Lefèvre.

The dancing class was well noticed in the papers, and was, I may say, a success.’ [iv]

M. Coulon’s dancing class was almost certainly painted in oils; this must be the watercolour study for it:

Albert Ludovici junior, M. Coulon’s dancing class, 1879, Mark Mitchell Paintings & Drawings

Ludovici met Walter Sickert fortuitously whilst painting in St Ives, and through him was introduced to Whistler; he then brought Whistler into the SBA. Ludovici, like his father before him, became one of the Society’s officials, and when Whistler was elected President of the SBA (1886-8) Ludovici was serving on its committee. In defiance of expectations by the old guard of the Society – as Ludovici tells it – Whistler took great interest in reforming and promoting the SBA, so that its exhibitions should no longer be cluttered ragbags of work but as minimally and elegantly hung as his own shows; this greatly increased its popularity and attendance at its exhibitions. Contact with Whistler was an important connection for the younger artist: they seem to have become firm friends, and in 1886 Whistler took The Times to task for ignoring one of Ludovici’s paintings on exhibition in the SBA. When Whistler was later elected President of the International Society, Ludovici became the Society’s delegate in France, so that the two men worked closely together – Whistler calling Albert, ‘My trusty Aide de Camp!’ He and Whistler remained friends and in 1899 visited Holland together with some of Ludovici’s pupils.

Albert Ludovici junior, The hansom cab, pastel, Christie’s, 6 March 2011

Albert Ludovici junior, The hansom cab, pastel, Christie’s, 6 March 2011

During his days as a student, and under the influence of his peers, Forain and Bastien Lepage, Ludovici had been attracted by Realism and then by Impressionism; but under the charismatic presence of Whistler himself, he was naturally drawn to the elements of aestheticism and Japonism in Whistler’s style. There is thus a lot of variation in style amongst the subjects he favoured. His education in Paris, with its cult of the flâneur and its intense interest in the lives of ordinary people in its streets and parks, awoke him to the street and park life of London; he produced a number of studies of social occasions, encounters in urban surroundings, and vivid evocations, like the pastel (above) of daily events.

Albert Ludovici junior, London socialites, Art market

Albert Ludovici junior, London socialites, Art market

In paintings such as London socialites, Ludovici has clearly been studying the way in which Whistler and Degas (themselves influenced by Japanese prints) articulated space in their compositions. The main group of figures has been shunted to the extreme right of the painting; the secondary group to the extreme left, and a large tract of empty lawn occupies the centre and lower left quarter of the picture. This radical and lively study of a London park in the summer is so completely different from the costume groups based on his father’s work that it’s hard to understand them as the work of the same hand.

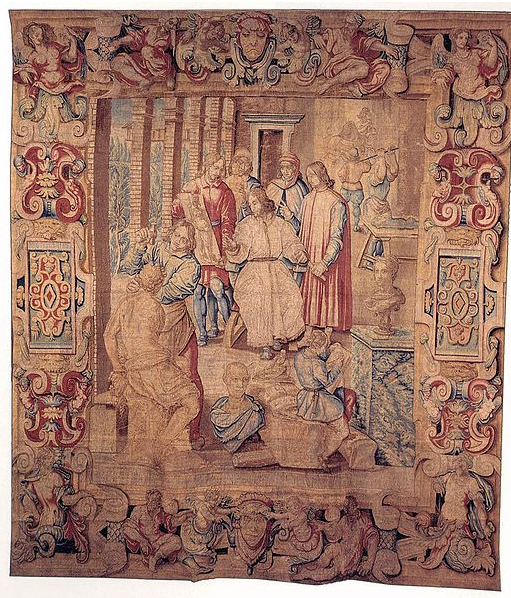

Albert Ludovici junior, The musical party, private collection

However, when examined the composition of a painting such as The musical party can be seen to have been constructed on similar lines to London socialites, with an asymmetrical emphasis, an area of empty space between the groups, and figures which are cut off by the frame. To modern eyes this is somewhat obscured by the ‘fancy dress’ aspect of the subject, and its relationship to the deplorable ‘drinking cardinal’ genre of painting: but if the figures were dressed in 1880s ballet skirts and some of the furniture removed, its relationship to Degas’s work would be clear.

Degas, The dancing class, 1871, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NewYork

Degas, The dancing class, 1871, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NewYork

Similarly, Ludovici’s Eton v. Harrow, an archetypical English scene, is greatly indebted to Degas’s Au courses… (French horse-racing) of c.1872:

Albert Ludovici junior, Eton v. Harrow, 1889, Marylebone Cricket Club, London

Degas, Au courses…, 1869, MFA, Boston

Degas, Au courses…, 1869, MFA, Boston

This interest in the work of the Impressionists, when it was still regarded as bizarre and outré in Britain, along with his knowledge of the Parisian art world and his fluency in French, made Ludovici the ideal liaison between the new International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers, when it was founded in Britain in 1898 with Whistler as its President, and the European and American artists whom it was hoped to lure into exhibiting in London. Ludovici was able, for example, to secure Manet’s Execution of the Emperor Maximilian (National Gallery) for exhibition in London, in its whole state, before it was cut up by the dealer Durand-Ruel.

Albert Ludovici junior, David Copperfield arrives in London, hand-coloured print, British Postal Museum

Albert Ludovici junior, David Copperfield arrives in London, hand-coloured print, British Postal Museum

At the same time he was producing commercial art in a very different vein: he illustrated a series of 16 scenes from Dickens’s novels, Dickens Coaching Scenes, which were published as prints at the end of the 19th century…

Albert Ludovici junior, May you have a quite too happy time, 1882, V & A

Albert Ludovici junior, May you have a quite too happy time, 1882, V & A

… and he also executed designs for greetings cards – here, a series from 1882 which parodies the Aesthetic Movement.

Ludovici’s London scenes had been greatly influenced by Whistler’s use of tone and colour; however, a contemporary critic remarked that Ludovici’s work sprang on ‘a lighter, gayer stem, that of his own artistic individuality’. He developed a visual shorthand in order to record these scenes en plein air; his first exhibition of this type of work, Dots, notes, spots, was held at the Dowdeswell Galleries, London, in 1888, and was favourably reviewed by George Bernard Shaw. He was a prolific artist; he exhibited at the Royal Academy from 1880, the Royal Society of British Artists from 1881, the Paris Salon from 1884, the New English Art Club from 1891, as well as the Grosvenor Gallery, the New Watercolour Society and the Société Internationale de la Peinture à l’Eau. He died in 1932.

Mary Kernahan, Nothing but nonsense, illustrated by ‘Tony Ludovici’, 1898

Mary Kernahan, Nothing but nonsense, illustrated by ‘Tony Ludovici’, 1898

Albert Ludovici junior had six children, only three of whom survived childhood. One of them, Anthony (1882-1971), seemed as though he might follow in the footsteps of his father and grandfather: when he was 16 and 17 he illustrated two children’s books, by Mary Kernahan and Lord Alfred Douglas, and when he was 24 he was employed as secretary to Rodin for several months. He served in the First World War, and was awarded the OBE; after this he began lecturing and writing on politics and philosophy, specifically in the light of Nietzsche’s work, much of which he translated. His stance was ultra-conservative, anti-feminist, and would now be considered slightly to the right of the BNP. He seems a strangely humourless and insular scion of his multi-national forebears, for all his pro-German attitude. The whole family now appears on Facebook, where a catalogue raisonné of the work of Albert senior and junior is gradually being assembled.

Albert Ludovici junior, The recital, Mark Mitchell Paintings & Drawings

Albert Ludovici junior, The recital, Mark Mitchell Paintings & Drawings

[i] A. Ludovici, An artist’s life in London and Paris 1870-1925, 1926, p. 10

[iii] Anne Jordan, Love well the hour: the life of Lady Colin Campbell, 2010

[iv] Ludovici, op.cit., p.70